By Paul Brown

Source: The Guardian. Thursday 4 September 2014

It is widely acknowledged that the planet’s political leaders and its people are currently failing to take enough action to prevent catastrophic climate change.

Next year, at the United Nations climate change conference in Paris, representatives of all the world’s countries will be hoping to reach a new deal to cut greenhouse gases and prevent the planet overheating dangerously. So far, there are no signs that their leaders have the political will to do so.

To try to speed up the process, the UN secretary general, Ban Ki-moon, has invited world leaders to UN headquarters in New York on 23 September for a grandly-named Climate Summit 2014.

He said at the last climate conference, in Warsaw last year, that he is deeply concerned about the lack of progress in signing up to new legally-binding targets to cut emissions.

If the summit is a success, then it means a new international deal to replace the Kyoto protocol will be probable in late 2015 in Paris. But if world leaders will not accept new targets for cutting emissions, and timetables to achieve them, then many believe that political progress is impossible.

Ban Ki-moon’s frustration about lack of progress is because politicians know the danger we are in, yet do nothing. World leaders have already agreed that there is no longer any serious scientific argument about the fact that the Earth is heating up and ? if no action is taken ? will exceed the 2C danger threshold.

It is also clear, Ban Ki-moon says, that the technologies already exist for the world to turn its back on fossil fuels and cut emissions of greenhouse gases to a safe level.

What the major countries cannot agree on is how the burden of taking action should be shared among the world’s 196 nations.

Ban Ki-moon already has the backing of more than half the countries in the world for his plan. These are the most vulnerable to climate change, and most are already being seriously affected.

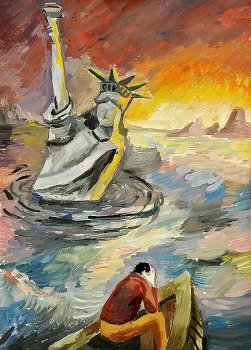

More than 100 countries meeting in Apia, Samoa, at the third UN conference on small island developing states, in their draft final statement, note with “grave concern” that world leaders’ pledges on the mitigation of greenhouse gases will not save them from catastrophic sea level rise, droughts, and forced migration. “We express profound alarm that emissions of greenhouse gases continue to rise globally.”

Many of them have long advocated a maximum temperature rise of 1.5C to prevent disaster for the most vulnerable nations, such as the Marshall Islands and the Maldives.

The draft ministerial statement says: “Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our time, and we express profound alarm that emissions of greenhouse gases continue to rise globally.

“We are deeply concerned that all countries, particularly developing countries, are vulnerable to the adverse impacts of climate change and are already experiencing an increase in such impacts, including persistent drought and extreme weather events, sea level rise, coastal erosion and ocean acidification, further threatening food security and efforts to eradicate poverty and achieve sustainable development.”

Speaking from Apia, Shirley Laban, the convenor of the Pacific Islands Climate Action Network, an NGO, said: “Unless we cut emissions now, and limit global warming to less than 1.5C, Pacific communities will reap devastating consequences for generations to come. Because of pollution we are not responsible for, we are facing catastrophic threats to our way of life.”

She called on all leaders attending the UN climate summit in New York to “use this historic opportunity to inject momentum into the global climate negotiations, and work to secure an ambitious global agreement in 2015”.

This is a tall order for a one-day summit, but Ban Ki-moon is expecting a whole series of announcements by major nations of new targets to cut greenhouse gases, and timetables to reach them.

There are encouraging signs in that the two largest emitters – China and the US – have been in talks, and both agree that action is a must. Even the previously reluctant Republicans in America now accept that climate change is a danger.

It is not yet known how many heads of state will attend the summit in person, or how many will be prepared to make real pledges.

At the end of the summit, the secretary general has said, he will sum up the proceedings. It will be a moment when many small island states and millions of people around the world will be hoping for better news.